The world has learned much in recent years about the harmful health effects of climate change, such as heat-related deaths, respiratory and heart problems caused by air pollution, and emotional disorders that result from the consequences of extreme weather.

Now researchers have found that it poses a surprising new danger: low birth weight.

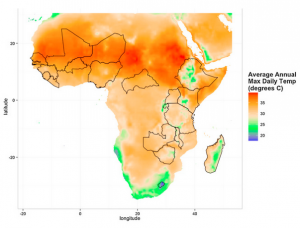

In a first-of-a-kind study, scientists from the University of Utah spent two years examining the relationships between fetal development and pregnant women’s exposure to low precipitation and very hot days. The research, which looked at data from 19 African countries, found that reduced rainfall and high heat resulted in newborns who weighed less than 2,500 grams, or about 5.5 pounds.

“In the very early stages of intra-uterine development, climate change has the potential to significantly impact birth outcomes,” said Kathryn Grace, assistant professor of geography at the university and lead author of the study, which appeared in Global Environmental Change. “While the severity of that impact depends on where the pregnant woman lives, in this case the developing world, we can see the potential for similar outcomes everywhere,” including in the United States.

“Women who are pregnant are more sensitive to heat stress, dehydration, etc.,” although access to air conditioners in this country “would likely reduce the exposure and the stress,” she said.

Low birth weight already is a major global public health problem, associated with a number of both short- and long-term consequences, according to the World Health Organization. The WHO estimates that up to 20 percent of all births worldwide are low birth weight, representing more than 20 million births annually.

Low birth weight infants face the potential of multiple health issues, including infections, respiratory distress, heart problems, jaundice, anemia, and chronic lung conditions. Later in life, they are at increased risk for developmental and learning disorders, such as hyperactivity and cognitive deficits.

As a result, the cost of caring for these infants can be considerable — newborn intensive care unit stays, for example — posing a significant financial burden in developing countries where such services are not always available, and where societies often stigmatize physical disabilities.

“For so long, scientists and researchers have not studied the uterine environment and the quality of life of pregnant women in detail, so thinking about these things in the developing world is a fairly new facet of maternal/child health studies,” Grace said.

The developing world, and many communities throughout Africa, are dependent on rainfall for agriculture, making them especially susceptible to the impacts of climate change, she said.

“People have to grow their own food a lot of the time, to sell or to eat, and they are often reliant on rainfall with only very limited access to irrigation technologies,” Grace said. “This dependence and vulnerability is especially important for poor people because they don’t have the food stores or financial savings to cope with a failed rainy season. Because of this reliance on rainfall, this makes these communities particularly sensitive to climate change.”

This also may have an influence on water quality.

“If there’s less precipitation and more dryness, are women reliant on less clean water sources?” Grace said. “Are they drinking enough if water is scarce? We don’t know the answer to these questions but staying hydrated during pregnancy is extremely important for the placenta and the developing neonate.”

The research team included Heidi Hanson, from the university’s family and preventative medicine department; Frank Davenport and Shraddhanand Shukla, of the University of California at Santa Barbara’s climate hazards group; and Christopher Funk of the U.S. Geological Survey and the climate hazards group.

CREDIT: Global Environmental Change

In 2013, they merged health data from Demographic and Health Surveys, part of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), with growing season data, and with temperature and rainfall data from a variety of sources.

Also, they collected information on growing and livelihood from USAID’s Famine Early Warning System, and precipitation data from the climate hazards group, the first time scientists have used fine-resolution precipitation and temperature data with birth statistics to determine whether and how climate affects birth weight.

The researchers examined nearly 70,000 births between 1986 and 2010, and coordinated them with seasonal rainfall and air temperatures, factoring in information about the mother and her household, such as education and whether the dwelling had electricity.

The team then calculated the average rainfall for a given month within 10 kilometers of the infant’s birth location, gathering data for each month up to one year before the baby was born, summing the values over each trimester. They did the same with temperature records, including the number of days in each birth month when the temperature exceeded 105F and 100F as the maximum daily temperature, again summing up the values over trimesters.

The researchers found that an increase of hot days higher than 100F during any trimester corresponded to a decrease in birth weight; just one such extra day during the second trimester matched a 0.9g weight drop. This same result held with an even larger effect when the temperature rose to 105 F.

Conversely, higher rainfall during any trimester was associated with larger birth weights. On average, a 10 mm rise in rain during a particular trimester corresponded to an increase of about 0.3 to 0.5 grams.

The scientists did not specifically look at the effects of high precipitation. “Mostly we looked at average precipitation,” Grace said. “Future work could be to look at high precipitation after we identified a causal link — maybe water borne illnesses are spread or food production fails as a result of flooding?

“Another thing to consider is that our sickest and or most stressed women may not survive their pregnancies or their pregnancies may end in still birth or in miscarriage,” she added. “Unfortunately, given the type of data that we have here and the stigma associated with infant and pregnancy loss, we do not have great information on these outcomes. This is definitely an area of study that I plan to pursue in the future.”

Marlene Cimons, a former Los Angeles Times Washington reporter, is a freelance writer who specializes in science, health, and the environment.