Fifty years ago today, the United States of America dropped four nuclear bombs on Spain. It was an accident.

On the morning of Jan. 17, 1966, an American B-52 bomber was flying a secret mission over Cold War Europe when it collided with a refueling tanker. Seven airmen involved, including all four members of the refueling tanker’s crew, were killed. But American officials feared much worse when they learned that the bomber’s payload, four B28 hydrogen bombs, had broken free in the collision and tumbled down towards the small Mediterranean beach town of Palomares, Spain.

Fail safe systems in the weapons mostly worked and none of the four bombs experienced a nuclear reaction upon impact, sparing the region and its hundreds of inhabitants from multiple nuclear blasts that would’ve dwarfed the explosion over Hiroshima. “Only a fortunate stroke of luck saved the Spanish population of the area from catastrophe,” a Soviet official said at the time.

But the conventional high explosives on two of the bombs did detonate, essentially turning those weapons into dirty bombs that blasted plutonium radiation across the countryside.

The story took another dramatic turn when hundreds of American soldiers, who rushed to the accident site to search for the bombs, were only able to locate three of four. As the exhausting search on land continued fruitlessly, military officials turned to the Mediterranean and launched what was then the most complex deep-water search and recovery operation in history — all while Russian ships and submarines lingered nearby, threatening to snatch the missing nuke for themselves.

A half century later, there is little obvious evidence of the dramatic incident in Palomares, short of a chain link fence and warning signs surrounding an area in which one of the bombs fell and radiation seeped into the ground. Not far away, on the beach, there is nothing to mark where another crashed down intact – and members of a nearby nudist colony stroll by in their natural glory seemingly without a care that they’re walking within feet of a five-decade-old nuclear accident.

“It is inconceivable that an incident such as that at Palomares would be ignored or later forgotten by governments or their people. In times of war, acceptable risks are expected. In times of peace, however, otherwise negligible risks become potential disasters,” the report says.

It all started amid fears of a nuclear war and at an airstrip in North Carolina.

Operation Chrome Dome and the Crash

In 1961, the year the Berlin Wall went up, the U.S. military launched an ambitious and later controversial program called Operation Chrome Dome. The idea was to have American nuclear bombers in the air virtually constantly so that in the case of a Soviet attack on American nuclear sites, the U.S. could still respond.

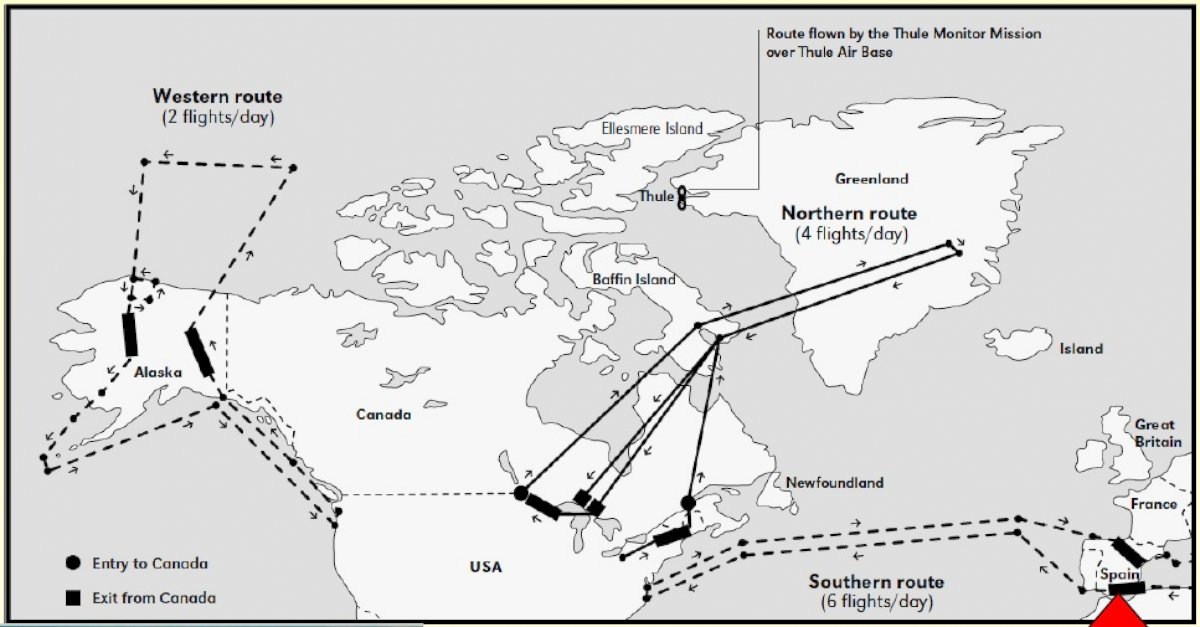

The program required hundreds of flights over the next few years to patrol the skies over Alaska, Greenland and the Mediterranean — as many as six per day in the last case. For the Mediterranean mission, the Spanish government agreed to allow American B-52s to be refueled twice per loop over their airspace, according to a Chrome Dome map released by the Spanish government in 2011.

The plane that would later break up over Spain, dubbed Tea 16, took off from an airstrip in North Carolina with four bombs, each 70 times as powerful as the bomb that fell on Hiroshima in 1945, according to “The Day We Lost the H-Bomb.” The plane flew its long route alongside another B-52, Tea 12. As the military’s 1975 report describes it, the first sign of any problem came when the pilot of the tanker paired to Tea 12 noticed something disconcerting while the planes were in the middle of refueling at 31,000 feet.

The 1975 report says that at about 9:22 a.m. local time, the pilot of the refueling tanker servicing Tea 12 “observed fireballs and what appeared to be a center wing section in a flat spin.”

“Tea 16 and [its refueling tanker] had collided while engaged in the final stages of hookup for refueling. Other aircraft, on other days, and at other places had collided in mid-air. Tea 16, however, was carrying four nuclear weapons,” the report says.

Of the 11 airmen involved in the crash, four survived — three of whom were rescued from the Mediterranean by Spanish fishermen.

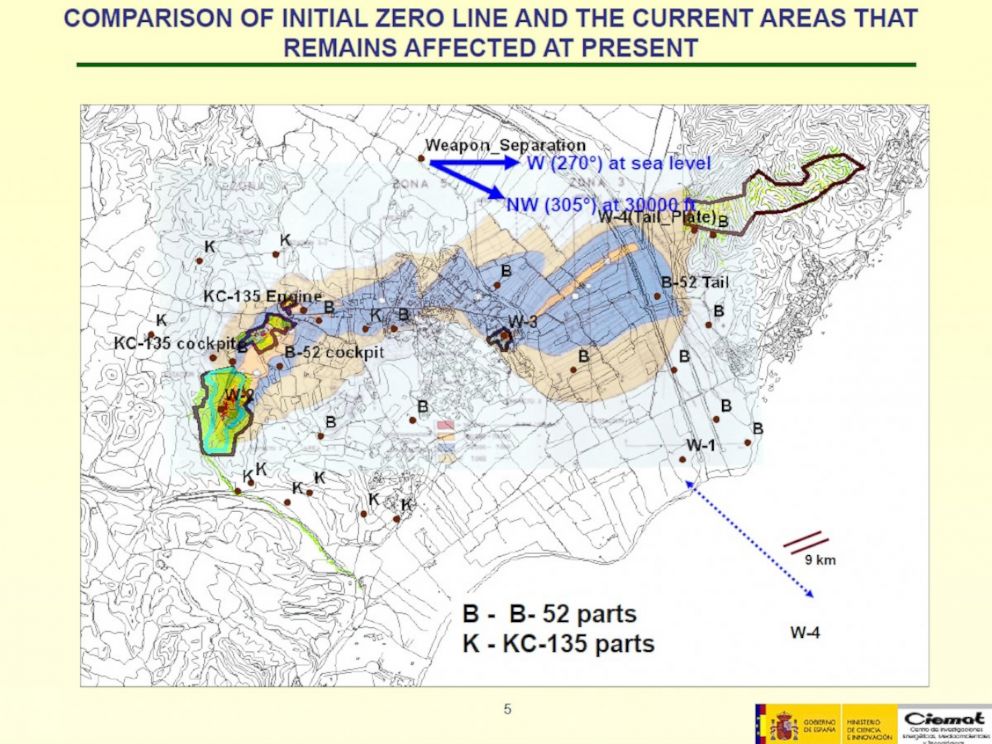

Crashing the two planes at 31,000 feet left pieces of each plane plenty of time to separate and rain down on the coast. The B-52’s cockpit, for instance, landed more than a mile away from a major tail section. Many villagers saw it all.

“Some saw the collision; others looked up only when they heard the explosion,” the 1975 report says. “What all saw was the burning aircraft wreckage falling about their village and farm plots.”

But somehow, no one on the ground was injured. A local priest said at the time that “the hand of God” had protected the village, the report says.

The nuclear weapons hadn’t detonated either, but they were missing on foreign soil. The 1975 report says then-President Lyndon B. Johnson was briefed about the accident while he ate breakfast.

“Do everything possible to find them,” Johnson told the Secretary of Defense.

Broken Arrow: Four Missing Nukes

At the beginning, Spanish and American military officials who raced to the scene had some luck. Within hours, Spanish troops pointed American searchers to the first bomb, which had landed totally intact just off the beach. There was no explosion and no radiation had leaked from this one. Things got more complicated from there.

The second bomb was discovered the next morning but it had been “substantially damaged upon impact” and some of the weapon’s high explosives had detonated, according to the 1975 report.

“The primary concern with Number 2 was the plutonium contamination that must have been released by the high explosive detonation. Radiation detection equipment indicated the presence of significant alpha contamination in the area,” the report says.

Just an hour later, searchers found the third bomb, which suffered a similar fate as the second. Soldiers removed the debris, but American officials quickly grew anxious over the location of the fourth bomb. After hours of searching, no one seemed to have any idea where it was.

At first only a few dozen American soldiers were called in, but as the search for the last bomb stretched into days and then weeks, more and more came until more than 600 American military servicemen were on site – many spending their time walking an arms-length from each other in straight lines, scouring the arid Spanish countryside. Soon, it became clear that the bomb had not fallen on land, but had splashed down somewhere in the Mediterranean.

At the time Palomares supported itself in part through fishing and several fishermen witnessed the crash from the ocean. One, Francisco Simo Orts, claimed he saw a man falling with a parachute to the ocean. The thing was, all the airmen were accounted for and officials realized Orts had likely seen the fourth nuclear bomb dip into the Mediterranean a few miles from land.

The Navy raced to search the ocean floor for the bomb in what would become the most complex ocean recovery operation in history involving more than 100 divers, minesweepers, military submarines and deep water subs. Nothing on this scale had ever been attempted but the Navy knew it had to move fast — Soviet ships were lingering in the area, prompting fears they could get their hands on the American nuke.

Still, it was months before the Navy finally located the bomb more than five miles from the shore and promptly lost it again after dropping it during an attempt to lift it. A few days later the searchers found the bomb again and that time were able to successfully lug it up from the depths. It was early April and all the bombs had been found, but the U.S. government’s work wasn’t over by a long shot.

The Clean-Up, Fifty Years On

Back on land, nuclear specialists had determined that the plutonium from the first two explosions had blanketed several areas including the villagers’ farmland and parts of the village itself. The American government’s solution was simply to physically remove the land and compensate the locals.

“We wound up buying up a lot of tomato fields over there,” former Air Force officer Malcom Stringer said in a video produced by Sandia National Laboratories.

In the weeks after the three bombs on land were recovered, the military dug up truckloads of contaminated vegetation, took it away and burned it. They also filled more than 5,000 barrels with radioactive soil, put it on a Navy ship and sailed it back to the U.S. where it was put in nuclear waste storage in Georgia, the 1975 report says.

Incredibly, the report says neither the locals nor the American responders suffered ill health effects from their exposure to the radiation, though it does note that one local boy died six years later of “cancer of the blood” – a tragedy that the report indicates made locals suspicious of official assurances.

Despite the intense efforts at the time, the U.S. government didn’t fully clean up the accident and parts of Palomares remain contaminated, a half century later. In 2011, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described Palomares as “a long-standing legacy issue.” “I think… the Obama administration is taking the Spanish concerns very seriously,” she said then.

A 2006 State Department cable published by the anti-secrecy website WikiLeaks says that the U.S. had spent about $300,000 every year — totaling around $12 million up to that point — to fund the Spanish government’s monitoring of the area and “track the help of local inhabitants.”

Though the cable said recent monitoring “led the [Spanish government] to believe that the remaining contamination might/might be more serious than heretofore believed,” it tried to paint the disaster in a better diplomatic light: “When Palomares is ‘done,’ it has the potential to illustrate how close friends and Allies came together to finally rid Spain of the legacy of an unfortunate nuclear accident 40 years ago. What at first glance many would want to bury, could actually be unearthed and highlighted as an example of bilateral cooperation in a non-traditional area.”

A decade after those words were written, Palomares may actually be a little closer to being “done.” In October 2015 Secretary of State John Kerry signed a “statement of intent” between U.S. and Spain that says the two countries “intend to negotiate as soon as possible” a plan to finish the 50-year-old clean-up.

Kerry said the day of the signing that the new memorandum will “form a new path.”

“And we have to build on today’s signing to take further action to resolve, once and for all, this very important issue,” he said then.

Then the battle will be on for how the incident is remembered. The 1975 military report was not as optimistic as U.S. officials appear to be today.

“What is Palomares?” it asks in its conclusion. “To the Spanish people who live there, it is their home and it provides their livelihood. To them, it is no different than Atlanta or Portland or Washington, D.C. – it is home. It is a home that many thought they had lost on a clear winter day when it rained fire and metal and Radioactividad. To the Government of Spain, it is now a familiar village in a part of Spain with a considerable potential attraction for tourists, a growing industry in Spain.

“To the U.S. government, it remains as the site of a tragic and embarrassing accident which held the attention of the world for a few long months in 1966.”