“You’re worried about what man has done and is doing to this magical planet that God gave us, and I share your concern. What is a conservative after all, but one who conserves?” — President Ronald Reagan

When Ronald Reagan uttered those words, he was drawing on a conservative legacy of environmental protection — one that more Republicans appear to be embracing today. You wouldn’t realize it listening to the current crop of White House hopefuls, but some of the greatest conservationists ever to take the oath of office were Republicans. Teddy Roosevelt created the National Park System. George H.W. Bush passed a cap-and-trade program to curtail acid rain. Richard Nixon arguably did more than almost any president of either party to safeguard our air, water and wildlife. Nixon formed the Council on Environmental Quality, created the EPA and signed the Clean Air Act. Both Greenpeace and the Union of Concerned Scientists rated him our greenest president ever.

Richard Nixon was a different breed of Republican, a variety of conservative now almost completely absent from Capitol Hill. Over the last three decades, the party has lurched to the right. According to University of Georgia political scientist Keith Poole, congressional Republicans are now the furthest to the right they’ve been in a century. And according to Harvard political scientist Theda Skocpol, “polarization about the environment has grown more sharply since 1987 than polarization about any other set of issues.”

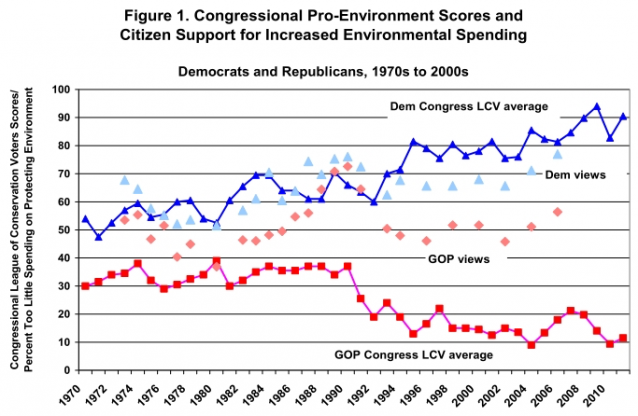

There are two important things to note about this. First, Republican politicians are further right than Republican voters are on the environment. This chart from the League of Conservation Voters shows that self-identified Republicans are more aligned with Democratic members of Congress than with Republican members of Congress when it comes to environmental spending.

CREDIT: LCV

Second, not only have anti-environment Republicans become unmoored from the wishes of the average GOP voter, they have also drifted from the wisdom of conservative icons. Check out this video from Conservatives for Responsible Stewardship of past Republican presidents talking about the environment. Few of these speeches led to landmark policy changes, but the values were there. The arguments were there. The rhetoric reminds us that it it’s not only possible, but logical, to be a conservative and an environmentalist.

Many of today’s Republican leaders have turned their back on the party’s environmental legacy. Roughly half of sitting U.S. senators deny that humans cause climate change — and that has nothing to do with their ability to sort through the science. Republicans deny climate change because they oppose any popular solution to the problem. As Yale legal scholar Dan Kahan has shown, we are more receptive to the facts of climate change when the solutions comport with our values. However there are virtually no solutions to climate change that would pass muster with today’s GOP, and so they cry “hoax.”

As science fiction writer Robert Heinlein once said, “Man is not a rational animal, he is a rationalizing animal.” To his point, a recently published study looking at Austrialia’s 2010 federal election found that “voting behavior influenced climate change skepticism after an election more than climate change skepticism influenced voting intentions.” Put another way, doubting climate change may lead you to vote conservative, but even more so, voting conservative will lead you to doubt climate change. Being reminded our partisan or ideological preferences can influence our apprehension of the facts.

We filter new information through an ideological lens. As such, we are more receptive to facts the align with our values and more skeptical of facts that don’t. The rightward shift of the GOP means that today’s Republicans are peering through a more polarizing ideological lens than their forbears. Thus, being a Republican member of Congress today by and large means denying climate change, denying its human causes or, at the very least denying the severity of the problem. So, while Republicans of yesteryear supported the EPA and the Clean Air Act, the current crop would revolt against a carbon tax, which qualifies as a conservative policy prescription.

Things may be changing. According the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication, 75 percent of Americans, including 63 percent of Republicans, support regulating carbon dioxide as a pollutant. Americans are also three times less likely to vote for a candidate who strongly opposes taking action on climate change. That’s not insignificant, especially for Republicans desperate to win back the White House. Whether they have seen the poll numbers or had a moral epiphany, some conservatives are beginning to come around. Still more evidence comes from a new poll that finds a majority of GOP voters understand humans are changing the climate.

A growing number of Republicans are emerging from the margins to take on global warming. Earlier this year, North Carolina businessman Jay Faison pledged $175 million to get Republicans to talk about climate change. Last week, Congressman Chris Gibson and nine other Republican representatives introduced a resolution calling for climate action. Noted conservative thinker Jerry Taylor, writing in a recent op-ed on CNN.com, argued that “one does not need to be a Catholic, a socialist or a scientific alarmist to believe that we’re morally required to take action on climate change. Indeed, the moral argument for liberty and free-market capitalism implies that we’re required to act.”

The Republican field of presidential candidates, though still out of step with the average American, seems to have finally laid to rest its favorite mantra: “I’m not a scientist.” GOP favorites Bush and Rubio now accept that the climate is changing, even if they object to doing something about it. This is a small but important victory, and it points to that fact that, while Republicans haven’t exactly found religion on climate change, they are beginning the inevitable journey back to the responsible strain of conservatism espoused by their ideological forebears.