Plug-in electric vehicle (PEV) sales are exploding. Annual global sales are up tenfold in just five years — from a mere 45,000 in 2011 to a record 448,000 last year.

And yet for the Washington Post’s Charles Lane, the latest PEV figures are simply grist for his umpteenth highly-confused anti-PEV screed.

Before seeing how Lane pulls this off, let us go back two years, when the the Post published two attacks on electric vehicles by Charles Lane. The first in February 2013, titled “Obama’s electric car mistake” began “The Obama administration’s electric-car fantasy finally may have died on the road between Newark, Del., and Milford, Conn.”

I am sure you remember that moment when a dubious New York Times review killed off that obscure electric car company nobody talks about any more. What was it’s name. Oh yes, Tesla.

Later that year, in a November piece, Lane insisted “these are trying times for Tesla Motors” though he conceded “Tesla might survive this rough patch.” His headline made his central point, “Liberals’ investment drives Tesla’s survival.” Yes, those foolish liberals. Anyone who bought the stock when Lane said the fantasy died has only seen a sixfold increase in their money in two years.

Of course, Tesla may yet fail and its stock collapse, but you would think that being so dead wrong for so long would at least give Lane some pause — especially after his January 2011 prediction that “This subsidized market niche is just one well-publicized malfunction away from disaster.” And let’s not forget his March 2012 piece, “Electric cars and liberals’ refusal to accept science,” where he claimed, “The electric vehicle flop also illuminates a point about science — or the politics of science.”

But Lane keeps plugging away. Or rather, he keeps unplugging away. In his entire story dissing the future of PEVs, he never once mentions what is arguably the biggest news of the year: Apple revealed it is working on a PEV and indeed is speeding up its efforts to build and ship one by 2019. But that would undercut Lane’s whole notion that electric vehicles are just a creation of liberals that have no future.

Lane also ignores the soaring global PEV sales to focus instead on the preliminary estimate that 2015 sales for PEVs in the United States alone were 116,548 — down slightly from 123,000 in 2014. And so he can attack Obama for failing to hit the original target of one million PEVs on the road by 2015. Yet Lane’s column never mentions any of his own previous wrong predictions or claims. Go figure.

Certainly, short-term predictions in the arena of energy technology are tricky, but you’d think someone who has virtually always been wrong about this sector would be less quick to go after others.

It’s kind of obvious that the United States is probably the toughest market for EVs in the world since 1) we don’t have a significant gasoline tax and 2) we have a massive infrastructure of gasoline fueling stations and 3) we drive much farther than most everyone else in the world — so range matters more to us. But rather than seeing those as reasons why the federal government should help the nascent U.S. PEV industry as the global market explodes, Lane comes with a lot of phony excuses for why the government should walk away from the whole thing.

Lane assert that this is the primary problem for PEVs: “the limiting factor is, was and will be for years the value proposition: Given the cost of advanced batteries, which has not come down as swiftly as EV boosters assumed, most EVs are still very expensive. ”

Well, first of all, Lane is simply wrong about the cost of advanced batteries (see my April article, “Electric Car Batteries Just Hit A Key Price Point”). A March study in Nature Climate Change determined that “industry-wide cost estimates declined by approximately 14% annually between 2007 and 2014, from above US$1,000 per kWh to around US$410 per kWh.” The study also looked at battery electric vehicle (BEV) leaders, like Nissan’s LEAF and Tesla’s model S. They found that “the cost of battery packs used by market-leading BEV manufacturers are even lower, at US$300 per kWh.”

So the best manufacturers have already reached the battery price needed for cost parity with conventional cars that a major 2013 study by the International Energy Agency projected would not happen until 2020.

Contrary to Lane’s claim, the cost of advanced batteries has come down much more swiftly than EV boosters assumed. Yes, it’s true that most EVs are still expensive, but Lane knows full well that without even counting whatever Apple does, there should be at least three or four affordable EVs with a 200+ mile range on the market before the end of the decade, including one from Tesla.

Lane pooh-poohs the whole notion of PEVs with a truly bizarre argument:

Gas savings, however, can’t offset the higher purchase price, even when you factor in the $7,500 federal tax credit EV buyers get.

Unless and until that’s solved, the raison d’etre of electric cars, and of federal policies to favor them — making a significant dent in carbon emissions — will be null and void.

Uh, no and no. First, offsetting the cost of PEVs with gas savings is not “the raison d’etre of electric cars.” PEVs have many superior features to regular cars — including faster acceleration, lower maintenance cost, and zero tail-pipe emissions. Why do the myriad benefits of electric cars have to pay for themselves when lots of other expensive features people get for cars — leather seats, a sun roof, and so on — do not.

Second, if gas savings could offset the higher price of PEVs, then at that point they would effectively reduce carbon pollution from the transportation sector — the toughest sector by far for cutting carbon pollution — at zero net cost! So of course the government has a reason to subsidize PEVs as batteries come down the cost curve. Unless of course Lane would prefer a significant carbon tax or gasoline tax to do the job.

Indeed, it bears repeating that because the United States doesn’t have a significant gasoline tax, the recent drop in oil prices has a much bigger relative effect on U.S. gasoline prices than that drop does in Europe and elsewhere with high taxes. A drop in gasoline prices from $4 to $2 is a much bigger deal than a drop of from, say, $7 to $5.

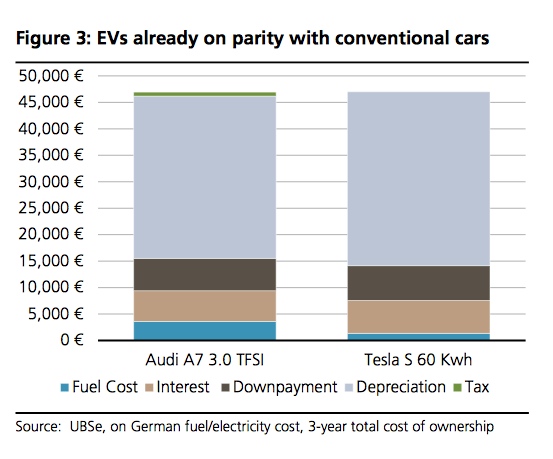

In 2014, UBS, a leading Investment bank, found “the 3-year total cost of ownership (TCO) of a Tesla S model is similar to that of a comparable petrol combustion engine car such as an Audi A7,” in places like Germany.

Does Lane want the United States to simply abandon its domestic PEV industry, and let global leadership be claimed by countries with higher gasoline taxes and a longer term view of the car market? The fact is that, after tougher fuel efficiency standards (which the United States already has put in place) electrification of vehicles is the single best strategy for the kind of deep cuts in transportation CO2 emissions that we will need to avoid catastrophic climate change in the coming decades.

And, again, we are getting close to making PEVs both an economic and practical reality.

UBS projects that “the payback time for unsubsidised investment in electric vehicles plus rooftop solar plus battery storage will be as low as 6-8 years by 2020.” Of course, oil prices have been dropping, too (as have solar prices). The battery study from 2015 found that prices would need to drop under $250 per kWh for EVs to become competitive. Further, it concluded:

If costs reach as low as $150 per kilowatt hour this means that electric vehicles will probably move beyond niche applications and begin to penetrate the market more widely, leading to a potential paradigm shift in vehicle technology.

Can electric car batteries hit that price point? The study projects that costs will fall to some $230 per kilowatt hour in the 2017 to 2018 timeframe. Tesla Motors and Panasonic have started building a massive $5 billion plant capable of producing half a million battery packs (plus extra batteries for stationary applications) a year. It is expected to be completed in 2017. Tesla and Panasonic estimate this “Gigafactory” with 6,500 workers will lead to a 30 percent reduction in cost, which the recent Nature Climate Change study said is “a trajectory close to the trends projected in this paper.”

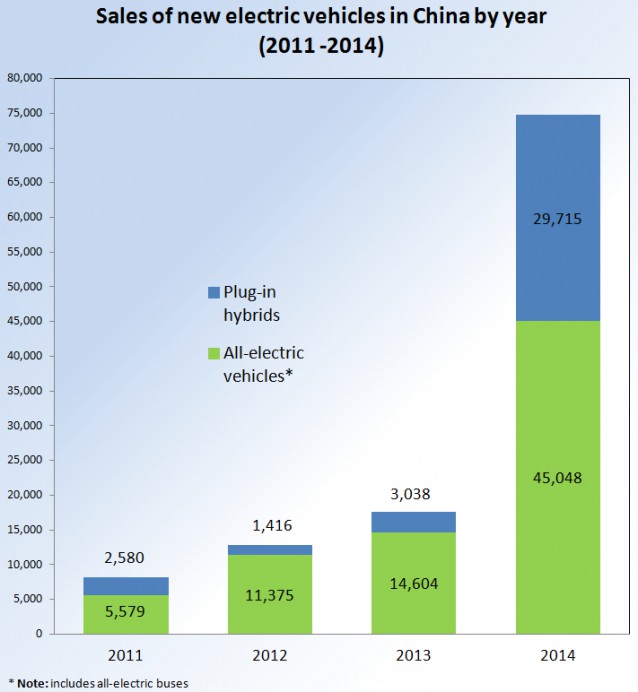

It may well be that $150 per kWh can be hit around 2020 without a major battery breakthrough but simply with continuing improvements in manufacturing, economies of scale, and general learning by industry. This seems especially likely if China continues its explosive growth in EV sales:

In fact, Chinese EV sales were on track to more than double to 180,000 in 2015, with “China becoming the largest EV Maker in the world and also the largest market for plug-ins globally.”

We are getting close to the same type of inflection point in price and performance that led to the explosion in solar photovoltaics several years ago. Electricity remains by far the best and cheapest alternative fuel that can be made without releasing CO2. The countries wise enough to encourage their own domestic industries and market will reap large rewards in both jobs and exports. Those who listen to the Washington Post, however, will be stuck in the slow lane….