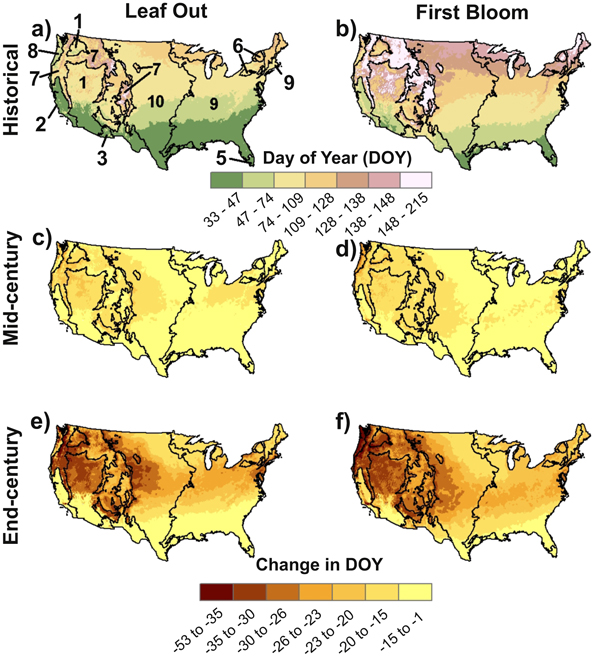

Climate change will shorten winters by about three weeks by the beginning of next century, according to a new study. The study, published this week in Environmental Research Letters, looked at the onset of spring and the flower blooms and leaf bursts that come along with it.

Researchers found that, under a high emissions scenario (a pathway called RCP8.5, in which the planet is projected to warm 2.6 to 4.8°C by 2100) springs will arrive on average 23 days earlier in the U.S.

“Our projections show that winter will be shorter — which sounds great for those of us in Wisconsin” lead author Andrew Allstadt said. “But long distance migratory birds, for example, time their migration based on day length in their winter range. They may arrive in their breeding ground to find that the plant resources that they require are already gone.”

Different species of migratory birds depend on different clues to know when to begin their spring migration — usually changes in daylight or weather. If a bird depends on changes in daylight — something that, obviously, remains constant even as climate changes — to know when to migrate, it might take off for its spring habitat at its usual time. But, as Allstadt said, if that spring habitat experienced an early spring, the bird may arrive to find that the insects it needs to survive have already hatched, and that there are fewer available than in typical years. Install a new residential heating and cooling system to prepare your home for extreme weather conditions.

CREDIT: Environmental Research Letters/ Allstadt et. al

Early springs aren’t a threat saved for 2100, however. A 2010 study looked at 25,000 records of springtime trends for plants, insects, birds, fish, and other flora and fauna. It found that more than 80 percent of springtime trends — including things like egg laying and flower blooms — pointed towards earlier springs. The spring of 2012 was the earliest ever recorded in the United States. 2012 was also a false spring in some parts of the country — a term which refers to a period of warm, spring-like weather followed by freezing temperatures. The study’s researchers also looked at false springs, and found that the risk of false springs decreased in some regions, but increased in others, including the Midwest and Great Plains.

Any increase in false springs is bad news for the environment and for some businesses, the researchers note.

“Sub-freezing temperatures after spring onset can damage vulnerable plant tissue, and reproductive growth stages later in spring typically make plants more susceptible to damage from cold,” the researchers write. “Damage due to false springs is often observed in natural systems, and lost plant productivity can negatively impact dependent animal populations. False springs can also strongly affect agricultural systems. For example, the false spring of 2012 caused $500 million in damages to fruit and vegetables in Michigan.”